The normalization of relations between Israel and Morocco and the U.S. recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara have stirred interest in the history of Morocco’s Jews, including during the Holocaust years.

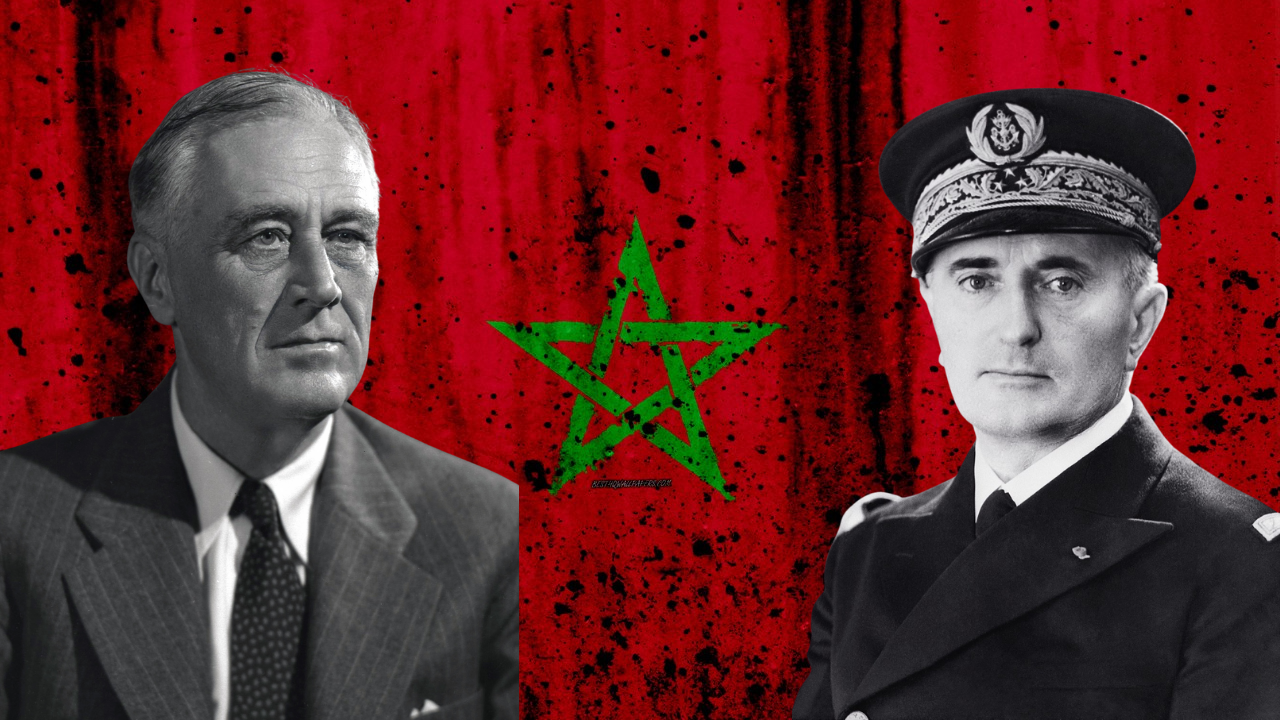

Unfortunately, some pundits, in their enthusiasm over these developments, have misleadingly portrayed the Allied liberation of North Africa in 1942 as the simultaneous liberation of the region’s Jews from their Nazi and Vichyite persecutors. That narrative papers over the harsh reality of what happened after the Allies’ victory. The full story of how President Franklin D. Roosevelt treated the Jews in Morocco and elsewhere in North Africa is a deeply troubling chapter in his administration’s history.

On November 8, 1942, American and British forces launched “Operation Torch,” the invasion of German-occupied Algeria and Morocco. In just eight days, the Allies defeated the Nazis and their Vichy French partners in the region. American Jews expected that the liberation of North Africa would also mean liberation for the 330,000 Jews there.

In 1870, the French colonial authorities in Algeria had issued the Cremieux Decree, which granted equal rights to that country’s Jews after centuries of mistreatment by Arab rulers (although it did not affect the Jews in neighboring Morocco). When the Vichyites took over North Africa in 1940, they abolished Cremieux and subjected all of the region’s Jews to a range of abuses, including restrictions on admission of Jews to many schools and professions, seizures of Jewish property and occasional pogroms by local Muslims that were tolerated by the government.

In 1941–1942, American Jewish newspapers carried disturbing reports that the Vichyites had built “huge concentration camps” in Morocco and Algeria to house thousands of Jewish slave laborers. The prisoners endured backbreaking work, random beatings by the guards, extreme overcrowding, poor sanitation, near-starvation and little or no medical care. According to one report, 150 Jews scheduled to be taken to the camps were so fearful of the conditions there that they resisted arrest and were executed en masse.

With the Allied victory, North African Jews — and their American coreligionists —expected the prisoners to be released and the Cremieux Decree reinstated for Jews living throughout the region. The American Jewish Congress optimistically predicted that the repeal of the Vichy-era anti-Jewish laws would follow the Allied occupation of North Africa “as the day follows the night.” But President Roosevelt had other plans.

MEET THE NEW BOSS, SAME AS THE OLD BOSS

At the beginning of “Operation Torch,” the Allies captured Admiral François Darlan, a senior Vichyite leader. FDR decided to leave Darlan in charge of the Allied-occupied North African territories in exchange for Darlan ordering his forces in Algiers to cease fire.

Many prominent liberals in the United States were appalled by this decision. “[It] sticks in the craw of majorities of the British and French, and of democrats everywhere, [that] we are employing a French Quisling as our deputy in the government of the first territory to be reoccupied,” an editorial in The New Republic protested.

The war was supposed to bring enlightened democracy to areas that had been under the boot of fascism — not keep the old tyrants in power.

Not only was Darlan still in power, but he also retained nearly all of the original senior officials of the local Vichy regime. Darlan did dismiss one Vichyite of note, Yves Chatel, the governor of Algeria — but promptly replaced him with Maurice Peyrouton, the very Vichy official who had signed the anti-Jewish laws of 1940. Together, Darlin and Peyrouton deep-sixed the Cremieux Decree and kept thousands of Jews in the slave labor camps.

Rumblings of concern began to surface in the American press. A December 17 editorial in the New York Timesexpressed doubt that Darlan really intended to bring about “the abrogation of anti-Jewish laws [and] release of prisoners and internees.” The editors of The New Republic asked on December 28, “Who controls French Africa, Darlan or the [Allies]? And if the latter, isn’t it high time we cleaned up the remnants of fascism that obviously still exist there?” An investigative report in the New York City newspaper PM on January 1 asserted that the Darlan regime was actively discriminating against Jews, and “thousands” remained “in concentration camps.”

President Roosevelt publicly claimed that he had already “asked for the abrogation of all laws and decrees inspired by Nazi governments or Nazi ideologists.” But he hadn’t. When reporters questioned him at a January 1, 1943 press conference, FDR replied, “I think most of the political prisoners are — have been released.” But they hadn’t.

NO RIGHTS FOR JEWS

The official transcript of FDR’s meeting with Major-General Charles Nogues, a leader of the post-Vichy regime, in Casablanca on January 17, 1943, provides some insight into the president’s thinking.

Nogues asked President Roosevelt about demands by North African Jews for voting rights. According to the stenographer, Roosevelt replied, “The answer to that was very simple, namely, that there just weren’t going to be any elections, so the Jews need not worry about the privilege of voting.”

The transcript continues, “The President stated that he felt the whole Jewish problem should be studied very carefully and that progress should be definitely planned. In other words, the number of Jews should be definitely limited to the percentage that the Jewish population in North Africa bears to the whole of the North African population.”

FDR explained that he wanted to make sure the Jews would not “overcrowd the professions.” He pointed to what he called “the specific and understandable complaints which the Germans bore towards the Jews in Germany, namely, that while they represented a small part of the population, over fifty percent of the lawyers, doctors, school teachers, college professors, etc. in Germany were Jews.”

In reality, Jews comprised about 16% of the lawyers, 11% of the doctors, 3% of the college professors and less than 1% of the schoolteachers in Germany. It’s striking that the president of the United States was so quick to believe the wildly exaggerated numbers — and to conclude that German hatred of Jews therefore was justified.

AMERICAN JEWS SPEAK OUT

As the weeks turned into months and as the fascists remained in power in North Africa, public criticism of the Roosevelt administration intensified.

Near-daily reports by I. F. Stone in PM featured headlines such as “U.S. Policy in North Africa: Why State Dept. Holds Up Repeal of Nuremberg Laws,” and “Hull Admits Anti-Fascist Prisoners Still Being Held in North Africa.”

Reports in the New York Times and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency’s Daily News Bulletin began citing, by name, the camps where North African Jews and political refugees were being enslaved — including one that was just five miles from where “American troops, dedicated to end government by concentration camp, live.”

American Jewish leaders were strongly supportive of President Roosevelt — and some 90% of Jews voted for him repeatedly — but his perpetuation of the persecution of North African Jews was just too much. On February 14, 1943, the American Jewish Congress and World Jewish Congress took the unprecedented step of publicly denouncing the president’s North Africa policy.

In a joint public statement, the two groups charged that “the anti-Jewish legacy of the Nazis remains intact in North Africa.” Despite three months having passed since the Allied liberation, only a few “grudging concessions have been made” to aid the Jews, while no changes “of an important character have been made in the[ir] political and economic situation.”

The statement reminded the president that he had pledged “action to insure that the four freedoms shall without further delay be declared as valid for all the peoples in North Africa, which means the total abrogation of all anti-Semitic laws and decrees and … the release of those of whatever race or nationality who are being detained because of their support of democracy and opposition to Nazi ideology.”

The remarkable statement from those two mainstream Jewish organizations was only slightly milder than the charge by Benzion Netanyahu, executive director of the militant U.S. Revisionist Zionists (and father of the current prime minister of Israel), that “the spirit of the Swastika hovers over the Stars and Stripes” in the administration of North Africa.

Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, the founder and longtime leader of the American Jewish Congress, then led a delegation to Washington to personally make their case directly to U.S. officials, and Wise’s co-chair, Dr. Nahum Goldmann, organized a group of prominent French exiles in the United States to present the State Department with a petition of their own.

The Union of American Hebrew Congregations (Reform) also called on the administration to intervene against the Vichyites. These protests induced a number of other prominent individuals to speak up, among them Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, the exiled French Jewish leader Baron Edouard de Rothschild and leaders of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

AGONIZING DELAYS

In March 1943 — more than four months after the Allies liberated Morocco and the rest of North Africa — the Roosevelt administration finally instructed the local authorities to repeal the anti-Jewish measures.

The implementation process, however, was agonizingly slow. In April, the forced labor camps in North Africa were officially shut down — yet, in reality, some of them continued operating well into the summer.

The Jewish quotas in schools and professions were only gradually phased out. It was not until October 20, 1943, that the Cremieux Decree was at last reinstated. After ten long months of presidential stalling and stonewalling, this disturbing chapter in American foreign policy finally came to a close.

The increased public interest in the history of North African Jewry is a welcome byproduct of Israeli-Moroccan normalization. But discussions of that history should include its less pleasant side; that part, too, has important lessons to offer.