Marvel’s newest superhero flick, “Black Panther” is breaking box office records, and for good reason. The revolutionary production of this movie aside, the film is an archetypal goldmine (or should I say “Vibranium mine”), chock full of explicit and implicit messages and symbolism that speak to the historical and lived experiences of, not only African peoples, but all persecuted and/or post-colonial nations pursuing auto-emancipation.

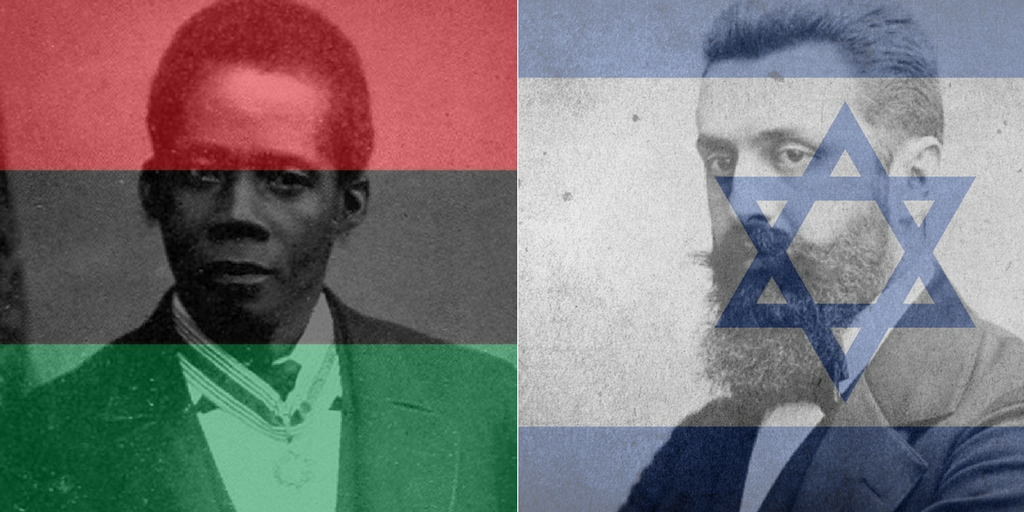

As an Israeli of a Caribbean background, an unapologetic Zionist and Pan-Africanist, I couldn’t help but appreciate this meaningful cinematic expression of internal conflicts that appear to be unique and highly relevant to the Jewish and African Diasporic experiences. A unique likeness, that both Binyamin Ze’ev Herzl (the father of modern Zionism) and Edward Wilmot Blyden (the father of Pan-Africanism) identified as sources for mutual inspiration in what may be the first and best case of meaningful intersectionality, which lead to revolutionary social movements. There are many aspects of this film that warrant in depth analysis and articulation, but four main points (detailed below) stood out to me as particularly relating to the shared African and Jewish experience with colonialism and slavery (at the hands of both European supremacists and Arab supremacists).

Early map of Wakanda (in blue) from the Marvel Comics Atlas Volume 1

First things first, however, much respect to the creators of the Black Panther character and universe, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Two Jews who utilized their artistic talent to express a quintessentially Jewish response to a world full of pain, oppression, and tyranny; to highlight the clash between good and evil, and give us heroes to inspire us in our individual and collective struggles. In the era of the civil rights movement, when Africa and African life was popularly viewed as inferior, they dared create a fictional African country untainted by colonialism, rich in super-natural resources (Vibranium), and a technological/military/political powerhouse. A narrative, that in the age of sh*thole gate, BLM, and the Libyan slave trade couldn’t be more relevant. A story, Director Ryan Coogler, was able to adapt to cinema with ease.

Wakanda’s internal ideological debate: isolationism vs interventionism. Upon the main character T’Challa’s coronation as the Black Panther (the title and superpower endowedon Wakanda’s hereditary monarchs), T’Challa is faced with the dilemma of defining Wakanda’s relationship with the international community. He inherited a Wakanda that managed to become a technological powerhouse and socially stable/thriving state on account of its isolationist policies; yet segments of the leadership (including T’Challa himself) feel morally obligated to share their success/freedom with the rest of Africa and the world. Being a tiny country with a bustling economy and high tech resources, yet paranoid from existential threats, the parallels with the reborn Jewish state are obvious.

Killmonger vs T’Challa’s vision for Tikkun Olam (repairing the world). A product of the African Diasporic experience, T’Challa’s Oakland born and raised principal nemesis in the movie, Erik Killmonger, is a Pan-African reflection of the European colonialism that oppresses his community. Like the European supremacists, Killmonger sees all Africans as defined (and united) by their appearance. Blaming Wakanda for not saving his community, Killmonger wants to use Wakanda’s resources to colonize the world, but this time for the benefit of indigenous Africans and other traditionally oppressed peoples. Conversely, T’Challa is fundamentally committed to his tribe (to his nation-state), yet he has universal aspirations to help solve the ills of the humanity. Not by force, but through leading by example. Rome vs Jerusalem. Uniformity vs Unity.

The complimentary relationship between spirituality and technology. Wakandan society is a powerful expression of progress guided (not stunted) by tradition. The responsibility to one’s ancestral culture and the ability to change reality with spiritual experience and/or technological advancement is an inspiring vision for all post-colonial indigenous societies and is fundamental to Torah Judaism’s prescription for a healthy Hebrew nation. Both Africans and Jews (African Jews included) have been historically denied their right to practice their indigenous faith and culture, which throughout their respective histories in the diaspora were generally depicted as primitive and even barbaric.

Wakanda: the Pan-African Zion, aligns with Achad Ha’Am and Rav Kook‘s vision for a spiritual revival that both provides former exiles with a life of substantive meaning while propelling us forward.

The temptation of radicalism. As demonstrated by the reaction of many of the characters in the film, it’s hard not to sympathize with and/or be drawn to Killmonger’s emotional rhetoric. It’s always easier to paint our complex reality in black and white. To prescribe simple solutions to complex problems. On the level of first or formative principles (good and evil, right and wrong), simplification is vital, but when it’s dogmatically applied to all contexts void of nuance it becomes dangerous. T’Challa identifies the destructive ends this approach would produce, and like Ze’ev Jabotinsky and Malcolm X (post Nation of Islam), in the movie he seeks to bring about a revolution for his people in a way that emphasizes the value of all of humanity.

By the same token, there have been times when both the Pan-Africanist and Zionist movements have ethically faltered in pursuing their goals (a topic for another piece), but none of this changes the fact that if the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice (as MLK famously said), the story of kidnapped and exiled Africans and Jews (African Jews included) must not end in tragedy, but triumph. That each of us can be a superhero in realizing the dreams of our ancestors and right the wrongs of history. To be free peoples, in our indigenous homelands.

As Malcolm X once put it, “Pan Africanism will do for the people of African descent all over the world, the same that Zionism has done for Jews all over the world.” The Zionist movement has revolutionized Jewish existence. It successfully restored some of history’s first victims of European colonialism and enslavement (at the hands of the Romans) to sovereignty in their indigenous homeland, revived the dying language of a dying people, helped bring the British Empire to its knees, and returned millions of exiles to their ancestral lands. Most importantly it restored Jewish pride in Jewishness. That for the first time in 2000 years a generation of Hebrews will be raised to know they have a home, that they are active participants in the world. As the father of Pan-Africanism, Edward Wilmot Blyden insightfully highlighted in his essay, “The Jewish Question,” Zionism successfully awakened the Jewish people from indifference to their persecution to an active sense of national responsibility, and this was precisely the effect he sought for Pan-Africanism to have on the African Diaspora. Likewise, Wakanda, as depicted in the “Black Panther” film, embodies the vision of Blyden and his Pan-Africanist descendants; a symbol from which Africans throughout the world can derive pride and strength.

The moral and physical struggle between T’Challa and Killmonger certainly exemplifies many of the similarities between Zionism and Pan-Africanism as indigenous rights’ movements; as does this quote from Killmonger during the movie that immediately brought to my mind images from both Masada and Igbo Landing:

“Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from ships, cause they knew death was better than bondage.”

Looking forward to Black Panther round two!

African American members of the “Black Panther Party” (coincidentally founded a few months after Stan Lee created the superhero) lining up to defend their community (top photo).

Hebrew soldiers of the IDF lining up to defend the Jewish State (bottom photo).

Published first in the Times of Israel.